Let’s think hypothetically for a moment. Imagine you have a friend or somebody you know and you’ve known them for so long that you’re positive they wouldn’t hurt a fly. Then, suddenly, you get a glimpse of the future and you learn that at some point, maybe a year from now or more, this friend will commit some kind of hideous crime. However it hasn’t happened yet in the time that you’re from. Instantly you’re transported back to the present with your friend who stares at you with uncertainty as you glare accusingly at him. Is your friend to be held accountable NOW for what he WILL do in the future?

Some people would argue that it is entirely unethical to hold someone accountable for what may (or may not) happen, while others might say that it’s simply best to nip it in the bud. That’s where the difference between knowing and understanding comes into play. Sure, you KNOW that your friend will commit[break] some perceived crime, but what are the circumstances surrounding him at that time. What led to this? Without any clear picture or perception for all sides at work, a person’s decision in this matter could possibly be just as destructive as whatever “future crime” this subject in question could commit.

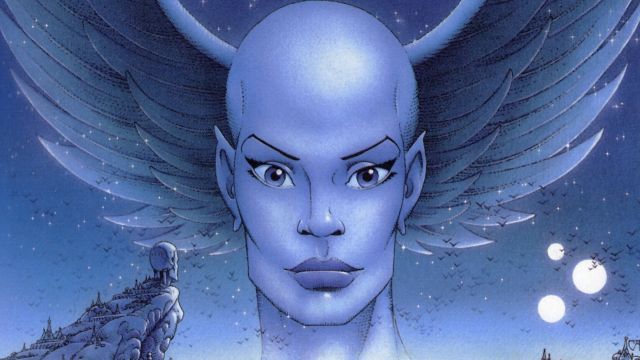

Done on a significantly larger budget than Fantastic Planet, another René Laloux film, Gandahar, or “Light Years” as it is known in this country, explores the aforementioned argument as well as themes of a hero’s journey and overcoming racism. The story revolves around the young prince Sylvain as he gradually learns the dark history of his people, the “benevolent” Gandaharians. What you ultimately end up with is a young man unsure if what he’s trying to preserve is worth saving. It’s an important lesson in questioning the world around you rather than taking everything everyone says as God’s truth.

Interactions with the horrifically malformed Gandaharians (dubbed “the Deformed”), are insightful not only in the audience’s perception of “evil,” but also the dangers of a contrived sense of superiority. Specifically, it is the danger of this inflated sense of self which entitles the “pure” Gandaharians to do as they please to the Deformed. As you later learn, the Deformed were made so by Gandaharian scientists, the alleged good guys. In fact, the more I learned about the Gandaharians, the less empathy I felt for them as the victims of a sinister plight. Sure, at the start of the film they were a peaceful society being brutally hunted by armies of robots from the future. However, their idyllic society hid a terrible secret and they were existing peacefully to the point of utter decadence. In a way, they themselves developed into a more antagonistic force in the story than the robots. Coincidentally, this army of robots was developed by a giant brain called Metamorphis, which was created and later abandoned by Gandaharian scientists. During the course of the story, it becomes clear that the Metamorphis has continued existing 1000 years into the future, and is the source of these time-traveling robots, however, when Sylvain attempts to assassinate the Metamorphis in the present, he is shocked to be met, not by a malicious murderer, but by a charming and introspective creature. This Metamorphis of the present has no wish to commit these future atrocities. It’s really one of those stories that, in addition to the philosophical and ethical debate, really blurs the line between good and evil and that’s something I think most people can appreciate.

The voice acting for the English dub was top-notch and I was absolutely awe-struck to learn of some of the famous voices in this production (Penn and Teller?!). However, be warned that there is one glaring difference between the original version of this film and the American version and it’s a musical one. I hope you like electronic keyboard because the American version is relentless with those artificial chimes that, at times, feel so utterly out of place with the setting and theme that an otherwise emotional moment comes off as laughably absurd.

Despite the less than pleasant score, there is absolutely no denying Laloux’s involvement in this project with the myriad of exotic and fantastic wildlife. While not nearly as diverse or astounding as the ecosystem of Fantastic Planet, the viewer is treated to the occasional candid vignette of alien wildlife. It doesn’t make the film any weaker for the experience as the tone of this film, in contrast to Laloux’s previous work, has a stronger emphasis on narrative. Instead, Laloux challenges us, the audience, to question what we have been taught to be the truth as well as considering the whole of a conflict rather than rallying to one side. The pacing and the presentation of these themes fail to obscure the overall narrative of the action making this a film to be enjoyed by both science fiction viewers and more introspective audiences alike.