Up until recently, I never understood the obsession with rearranging the timeline in a story. Starting a movie at the end and then starting from the beginning from the closing scene always confused and disoriented me. By the time I realized what was going on, I had missed critical information occurring in the middle of the movie (which was now the beginning of the story). While I believe that such a method forces the viewer to pay attention and “put two and two together,” I don’t think it’s entirely necessary; often times I find it ancillary. I understand the need to make the audience focus, but I’ve often seen this method do more damage than good when done frivolously.

When I was handed Hell Ride, I knew what to expect when I saw the obligatory “Quentin Tarantino Presents” on the cover. Even though that spaz didn’t necessarily make the film, at some point during production he had his grubby little fingers in it. Something about this movie was going to be awkward, “balls to the wall” absurd, violent, and/or horridly out of sequence. I was correct about the last part, but the rest is a surprisingly coherent narrative about trust, brotherhood, and scantily-clad women who throw themselves at you for riding a “hog.” What I experienced in Hell Ride is difficult to explain. While they did tell the story starting with the middle of the movie, they did such a good job of planting seeds of intrigue and mystery that it actually served more to hook the viewer than alienate him. Messing with the story’s timeline actually served to make the story more interesting, in this case, and flashbacks, while frequent, never really repeated themselves and were always present to hold your hand in case you forgot an important detail.

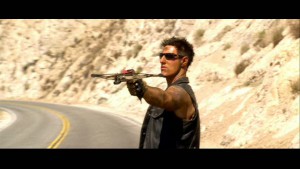

The movie starts out with the main character, Pistolero (Larry Bishop), lying in the middle of the desert after having been shot in the gut with an arrow. This scene is actually the middle of the film and occurs about 40 minutes in. Starting a movie this way not only raises questions about how this happened, but the viewer is intrigued and enticed to surmise who could have done this and why. As the movie continues with events that happened hours earlier, we are introduced to numerous characters, some who wield arrow-firing weapons, and we’re constantly thinking and trying to figure out “whodunnit.”

Hell Ride never completely takes itself seriously and constantly reminds you that it is a fictional narrative, completely detached from the world around you. While some philosophers might say that this destroys the illusion one creates in their mind while watching, this type of handling ensures that the message of the film is carried across without being too preachy. Whenever characters of note make their appearances, time stops and a logo of their biker affiliation and their nickname appear next to them onscreen. With each principal character having their own blatant introduction and defining scene, it’s very easy for the audience to keep track of the numerous characters without getting confused.

As with many films of this type, it seeks to shock and stimulate your mind with its atmosphere of depravity. Women are portrayed as objects of lust, frequently appearing nude or working as sultry waitresses in houses of ill-repute. Men are stoic and snarky with an unspoken code of brotherhood that results in violent retribution should they be crossed. For better or worse, the film ventures more into the realm of exploitation and vulgarity while attempting to tell an intricate story of revenge, honor, and redemption.

Telling a story out of sequence is nothing new, and while the shtick has been done to death, Hell Ride manages to do a pretty good job of it. There are easily several decades of history prior to the events in the film, and not only are the events relevant, but they also shape and develop the characters in the present. Character relationships are deep and intricate as a result. At no point do the flashbacks feel tacked-on or unnecessary.